Lew Rosenbaum

Whatever holiday you celebrate at the end of December, one thing is mathematically certain in the northern North America: the days will get colder, but the daylight hours will get progressively longer. One reason I look forward to December 21: I start counting the minutes of increasing daylight, a light shone into the world. This is all distinct from the various holiday hubbubs, gift giving, and Salvation Army Santas ringing their bells. For most of my life I have found the holidays alienating at best, “Merry Christmas” a taunt at least as often as a blessing. I imagine the memory from my childhood in a New Haven department store with customers fighting each other to get what shirt, or handbag, or socks were on the bargain table. The myth that suicides go up during December made sense to me.

Poet/novelist Richard Krawiec writes Sunday morning meditations or “homilies” of a sort. Reading them as I arise has become a blessed weekly opportunity to contemplate. He opened his Dec. 17 piece with these words: “I don’t care if you think this sentimental, but throughout my life I have often found this season to be magical.” Sentimentality is not a problem for me. After all, I love Tchaikovsky. But the season is not always magical, and Richard explores some of these contradictory elements. It triggered me to explore my own relationship to the season, a complicated one. None of the following is intended as a retort to Richard, whose explication is brilliant.

First of all, as a child this season was not quite somber – but certainly isolating. Growing up in a non-religious Jewish family in the 1940s and 1950s, I couldn’t understand why my classmates were getting presents and I wasn’t. All the celebratory stuff was about other people. I did not share in that. Except for the vacation from school part. Thank god Jesus was born. Otherwise we wouldn’t have two weeks off during the snowy time of year.

Chanukah is not a major religious holiday and it wasn’t much of a commercial holiday then either. So, no menorah, no presents, usually “Chanukah geldt,” which were coin-like circles of chocolate in a gold foil. On top of all that, my birthday fell on December 10. My parents, whose main goal in life was to continue to put food on the table and keep a roof over our heads, never had enough for additional December presents. I didn’t get “Santa Claus,” and I didn’t get all the merriment. The merriest time was a Sunday morning, maybe for my birthday, bundling up to walk with my father to Fox’s Deli on Whalley Ave. or to Glick’s on Legion Ave. We’d stand in line at the counter inside, bask in the warmth and the smells of corned beef, edging up to order a half dozen bagels and a quarter pound of lox and maybe a piece of whitefish. And then back home to devour the breakfast treat.

On the other hand, my parents would on occasion take me to New York (we lived in New Haven, CT – a short train ride to the city) for the New Year celebrations. We would stay in the Hotel Latham, a cheap hotel, and visit relatives and friends, stop by Dauber and Pine’s bookstore, legendary in New York’s book row, where my father had once worked. We might go to a Yiddish theater production, see the Museum of Natural History, and experience the crowds on January 1. That was magical, exhilarating – Times Square, the lights, the noise, the midnight joy of the New Year, sometimes by the sheer size of it, frightening. A new year, though I didn’t see any difference the next day.

When I fled New Haven for college in Los Angeles, I settled in at the University of Southern California. I no longer recognized winter: no snow on the ground, temperatures never below freezing, actually swimming in the ocean on January 1. My brother-in-law and sister, who had moved to the Hollywood hills with their three children, confused and perplexed me: They really celebrated Christmas.

He was a lawyer, and on his behalf she would host a holiday party for their business friends. Los Angeles has a large, thriving Jewish population. Still, it was a small segment of the total population, and a successful legal practice meant breaking out of that isolation. To make more business friends, they appealed to the non-Jewish business community. Their living room, with its 14-foot ceiling, accommodated a substantial real Christmas tree, which required a ladder to reach to the top for decorating purposes. And then, on Xmas morning, their three children would appear around the tree to examine what looked to me like an overwhelming assortment of presents and, ultimately, open them and exclaim happily on the findings. I even found presents for me under the tree, and I began to shop for Christmas presents (usually books for the kids). The world of such abundant showering of gifts still did not seem real. I took photos.

My tuition scholarship to USC required that I work for the University. I was assigned to the employment office, where I put in 10 hours a week (and more during break periods). Hopeful graduates paraded through to avail themselves of the dangling carrot of a good paying job.

My wage (during holiday or summer breaks) was $1.00 per hour. The office had three full time personnel: Florence B Watts, the ancient overlord of the department who ruled from the building next to our workplace; Clarion Modell, who as office manager occupied an office on the second floor of our building (a repurposed house); and Mary Pershall, who had a degree in counseling and a desk of her own on the first floor. Mary had had polio as a child and as an adult walked with two crutches. At the end of the workday she’d often brandish one crutch in her fist, and leaving her desk, exclaim: “Another day, another dollar, and that’s about the size of it.” Part timers rotated through, mostly students trying to pick up a little extra cash. From time to time they gave a fourth person full time work, as long as he stayed sober.

Our tasks were to match student or graduate job applicants with job offers. My job was coding applicant punch cards depending on what kind of jobs they wanted, and then pulling matching cards for applicants when we got a job offering. We didn’t have enough hot-shot engineers in our files to fill all the Jet Propulsion Labs, Autonetics, Hughes Aircraft, and North American Airlines aerospace openings. Few of the people looking for secretarial jobs could type fast enough for the jobs we had. The whole thing seemed futile. Mary and we part-timers enjoyed a camaraderie of sorts – we were the comrades of the left-outs and the have-nots – so even when we celebrated a modest office party, the holiday season seemed a little desolate.

USC was known for two main degree programs. A BA or BS in business was a ticket to corporate Southern California; graduating in football was a good chance for a pro career. The football team was frequently in the Rose Bowl, and as a student I got cheap tickets to the extravaganza. The year was 1963. I took the bus from Hollywood to Pasadena early enough to watch the Rose Parade in the morning, then walk to the Rose Bowl, and finally get the return bus when the game was over. The parade proceeded up the mansion-lined Orange Grove Blvd and then along the fleabag hotel lined strip of Colorado Ave. The contrast was even more noticeable on the walk through the north side of Pasadena, along Fair Oaks Ave., to the Rose Bowl itself. Talk about desolate during the holidays. As an aside, USC beat Wisconsin 42 to 37 in one of the most exciting Rose Bowl games ever.

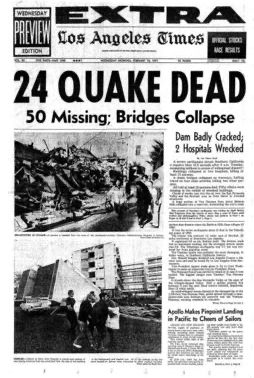

Six years later I was a social worker in Pasadena, CA. I had my BS from USC, I’d witnessed the 1965 Watts rebellion, I’d met and worked with San Joaquin Valley farm-workers, their medical clinic and the grape boycott. I had not graduated from USC medical school, I’d taken an unauthorized trip to Cuba, and witnessed the attack by the LAPD on the Los Angeles Black Panther headquarters. The attack on the Panthers in December 1969 made that year especially desperate. From the welfare office on Holly St. in Pasadena, you could throw a stone and hit the welfare, fleabag, Taylor hotel on Colorado Ave.

The Taylor ran a scam like other welfare hotels around the County. When a person presented a voucher for a week’s room, the Taylor would offer them cash for the voucher at a discounted rate – let’s say 50% of the face value of $16.00. For the hotels they were redeemable at face value from Bank of America, which held the welfare department account. A neat little profit for the hotel, plus they could still rent the room. The week before the Rose Bowl, the Pasadena police rounded up the welfare recipients and homeless on the streets and swept them out of town so the tourists wouldn’t see them. Season’s greetings.

Two or three blocks from the welfare office stood the restaurant where we would send clients with vouchers for their meals (if they did not have a place to cook). $10.50 was supposed to provide meals for a week at the B&C Café. New Year’s Eve, 1969, with the smell of tear gas still in my nostrils from the attack on the Panthers; with the knowledge of the circus about to appear in the streets of Pasadena to celebrate the Rose Bowl; and with the understanding that many of the recipients I had been dealing with were unceremoniously given literally the bum’s rush of town; I had the bleakest meal of my life at the B&C café, where the few people gathered for dinner ate silently, morosely. Apparently lots of people don’t find the season a time to rejoice.

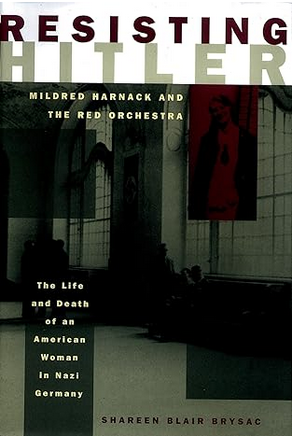

My years as a bookseller, beginning in the mid 1970s, gave me another contradictory view of the season. Being a bookseller at Midnight Special Books in Santa Monica, CA and later at Guild Books in Chicago opened up a new way of looking at Xmas. First of all, a lot more people came in the stores in that month between Thanksgiving and Xmas. People I had come to know during the year, and who used the opportunity to engage in the kind of meaningful discussion that comes about around good books and good company. Second, their attitude was more upbeat in the season than the rest of the year, and that was contagious. But third, and most important, since most of our “customers” were also active in some social movement they were in the store looking for a recommendation about a book that we were passionate about. That we-the-booksellers and they-the-customers shared a common interest in. It was a time when we could “sell” our cherished books. As a retailer, I understood that if we didn’t sell a lot in these two months before New Year, we would not be around next year to sell books at all. But for the bookseller at Guild and Midnight Special, the quality was as important as the quantity. “Pick up the book, It is a weapon,” as Bertolt Brecht said.

I don’t even remember if the standard greeting was Happy Holidays or Merry Xmas.

My ten years as Barnes & Noble were a mirror image of this. Customers flooded into the store, usually with very friendly, smiling attitude. However, as it grew closer to the day, the outlook became more frenetic than upbeat. And the corporate nature of the retail atmosphere made our lives more frenetic as well – understaffed, running from one customer to the next, overtime and working both weekend days. As much as it was clear that people were there to buy, and did walk out with stacks of everything conceivable, every year reinforced one thing: my cherished books were not necessarily what they wanted. I “sold” lots of books, but I rarely convinced anyone about a book. And then, everyone told me Merry Christmas, Merry Christmas, Merry Christmas, ad nauseam. By the time I was fired from B&N I came to hate the essence of the season: that everyone assumed I was Christian, or that everyone celebrated Xmas. In response to Merry Christmas I grimaced back through a thin-lipped smile, Happy Holidays. (A decade later my Catholic mother-in-law (who had known me for 25 years) said she thought Jewish people believed in Jesus Christ. Didn’t everyone? ).

Magic? Those years at Midnight Special and Guild, where I felt I was actually making a difference did have a magical essence. Now, as bombs rain on Gaza and one of my grandkids just took a plea deal in the Dept. of Corrections and over 20,000 people seeking asylum have been shipped to Chicago’s overburdened streets, Merry Christmas seems like a curse and Season’s Greetings a cruel joke.

In his essay, Richard Krawiec introduced Langston Hughes’ picture of this side of Xmas with these words: “During Christmas, wars and poverty do not take a holiday. They never have.”

Merry Christmas, China

From the gun-boats in the river,

Ten-inch shells for Christmas gifts,

And peace on earth forever.

Merry Christmas, India,

To Gandhi in his cell,

And to you down-and-outers,

(“Due to economic laws”)

Oh, eat, drink, and be merry

With a bread-line Santa Claus –

Langston Hughes, 1930

But there is another side to the story.

We do have something to celebrate this year as never before. Never before have so many people – including Jewish people – been willing to take on the Israeli established organizations and support the Palestinian cause as their own; despite all efforts to divide us, the voices in Chicago raised in defense of the asylum seekers is unprecedented; the fight to end our carceral system has expanded, the rebellions following the murder of George Floyd continue to smolder and wait, perhaps just below the surface. These are the greetings of the season, harbingers of a new society that means peace and liberation for all.