Who Shall Inherit the Earth?

by Lew Rosenbaum

[First of all: apologies for the reproductions here, which come from my “phone” at the exhibit and consequently have all the defects associated with that. Second, this exhibit has now left Chicago and will be opening at MoMA in New York in October, 2018; then at LACMA in Los Angeles in February, 2019. Do not miss this exhibit. Last, with gratitude for having had the opportunity to meet Frances Barrett White, and her two children Jessica and Ian, and be welcomed into her home in the mid 1980s. — LR]

“Think! Think about what you’re tryin’ to do to me.” These lyrics from the song written by Aretha Franklin’s (1968, Aretha Now) are chasing through my head as I mull over my response to seeing the Charles White Retrospective exhibit in the Art Institute of Chicago. For the second time. And I don’t go to exhibits more than once. But I did make time for this exhibit, and these Aretha-lyrics come to me because of something Danny Alexander wrote. It’s about the artist and the thought processes that galvanize the artist’s work, whether music to the ear or the visual music on paper and other media. It’s what the artist is telling the listener or viewer. I am not skilled in the language of visual art, so I will leave it to others to comment on the techniques, of which Charles White was a master. The force of the paintings, etchings, linocuts, drawings — everything — moved me to tears throughout the galleries. Often tears of joy at experiencing something that struck so close to home that it felt like a personal communication, an embrace by what art should be conveying.

Thinking. How do you capture brain waves on paper? The text accompanying “Awaken from the Unknown recalls White’s transformation after reading Alain Locke’s 1925 The New Negro anthology, and finding there “a new world of facts and ideas in diametric opposition to what was being taught in the classrooms and text-books as unquestionable truth.” Maybe you start there, recalling what it was like, when your mother dropped you

Awaken from the Unknowing – Charles White (1961)

off at the public library (it was at the Chicago Cultural Center then) at 7 or 8 years old, and you reconstructed the real world from what you read there, and then walked the few blocks to the Art Institute, wandering the halls, where you said your found the work of Winslow Homer particularly influential. At least that’s what Charles White did and said, and in this piece I see myself and imagine the subject of this piece on a road to discovery, perhaps after work, exhausted, and falling asleep over the piles of newspapers, just like I have done many times. Falling asleep in the process of awakening, kind of a visual pun, I suppose. She’s been asleep and here is the key to awakening. Discovering the new ideas that transform. Here’s a new idea that transforms: “Think! And let yourself be free!”

Much earlier in his life, Charles White contemplated what brought him to his own understanding. He painted these two pieces in 1942, “Hear This” and “This, My Brother.”

This My Brother – Charles White (1942)

Both these pieces speak to a kind of awakening, or different stages of awakening. Referring to the title of the novel by John Rood, call “This My Brother” social consciousness, the discovery not only that classes exist, but that the workers as a class, in this case the miners, have a class enemy. This form of learning comes directly from the struggle, the battles for a better life. It evolves out of what is often called the “spontaneous movement,” though it should be clear that there is very little spontaneity even in this process. But then you have “Hear This,” in which the two figures are engaged in, even fighting over, the written word. One figure, grasping a book, tries to convince the other about its point of view; the other, seems unconvinced

Hear This – Charles White (1942)

(the text next to the paintings implies that it referred to White’s own experience learning about the social struggle from communists). They (the man with the book, the communists) introduced something new, something that came from outside the struggle itself, something that reflected that particular role that workers play in transforming society. Changing the social order is fundamentally different from the practical role workers have in fighting for better wages and working conditions. Looking at these two pieces gives a kind of visual representation of the difference between the school of the strike struggle and the school of revolutionary propaganda. And, of course, the relation between the two: without the learning that comes from the practical struggle, the propaganda remains so much sectarian jargon. But in these two paintings, along with that dramatic “Awaken” piece, comes a visual lightning bolt that 100 pages of explanation can never transmit so dramatically (or, dare I say, graphically).

* * * * *

Let’s take a step backward, talk about Charles White and this “communism” thing. The text accompanying the exhibit alludes to it in a number of places aside from what is noted above. For example, at the entrance to the exhibit, the text calls him a “political leftist who championed the rights of the working class.” The text accompanying his mural work reads: “White aligned himself with a group of leftist artists [in Chicago] who drew attention to inequities in American society in order to effect social change.” It was much more than that. Frances Barrett White wrote a memoir of her life with Charles White (Reaches of the Heart, Barricade Books, 1994, o.p.). “Charlie’s art teachers,” she writes, “encouraged his talent and twice entered his work in statewide competitions. Both times he won, and both times when he appeared to receive the awards, they were denied to him.” It was a mistake, he was told. Someone else had actually won. “By the time he was fifteen, Charlie had read . . . The New Negro many times. The knowledge of his culture he found there was overwhelming. . .” He began to dislike school intensely, stopped attending, and found as an alternative the “Arts Crafts Guild, a group of black artists who met every Sunday. It changed the direction of his art.” In his early meanderings in the Art Institute, he had been influenced by Winslow Homer and the Hudson River School, and this translated into paying attention to landscapes. Now, with the Arts Crafts Guild, he took his easel “into the neighborhoods and painted people. Black people. . . on the streets, on the stoops of broken-down buildings, and hanging up their laundry.” Winning another statewide competition this time brought him a one-year scholarship to the Art Institute.

He completed his course work in 1938, a time when the depression still ravaged the streets of the U.S. The government found work for artists through the Works Progress Administration; numerous arts organizations brought writers and people in the theater and visual artists together to talk about their individual crafts and also how to address the issues raised by the depression. Along with the fight to survive came the attempt to grapple with the issues intellectually. Within this ferment communists brought their understanding of the drive toward World War that was seizing Europe. In the John Reed Clubs and later the American Writers Congress, authors debated how to stop the threatening war. Artists joined the Lincoln Brigade of the International Brigades to stop the fascist offensive in Spain. Artists looked to Mexico and the mural movement there and the involvement of artists in workers’ struggles. The current exhibit mentions only four murals he worked on; but Fran White relates that he “joined the WPA where he painted murals in post offices, libraries, and public buildings throughout the country, never staying in one place any longer than the work required.” In 1941 he married Elizabeth Catlett, a prominent Black sculptor, and in 1942 won a $2,000 fellowship to study the role of the Negro in the development of America. The two of them spent the next two years in the American South studying and sketching subjects from Black life.

Drafted into the army in 1944, he suggested to his Sergeant that he could use his skills as a combat artist. He was therefore assigned to the Jefferson Barracks in Missouri, where “he painted the mess hall, the tables, the benches, and the chairs again and again, always using the same color of green paint.” During a flood he and his fellow soldiers in the segregated battalion filled and moved sandbags, as if in a prison gang. And shortly thereafter he came down with tuberculosis, which affected him for the rest of his life.

These are some of the events that formed the context of his early life for the intellectual development that brought him, for example, to be an art director at Wo-Chi-Ca, or Workers’ Children’s Camp in upstate New York (where he first met Frances Barrett). Led him to form binding friendships with some of the most prominent artists of the time — Margaret Burroughs, Gordon Parks, and Rockwell Kent — and, when he settled in New York, to form an organization, the Committee for the Negro in the Arts, in the early 1950s, including Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Langston Hughes, and Oscar Hammerstein. He appealed to friends in the Thomas Jefferson School of Marxist Studies (the Communist Party workers’ school) for help finding a place for an interracial couple to rent an apartment in New York. These cohorts, his colleagues, his confreres stoked that intellectual fire and helped him conclude, as the text to the exhibit proclaims, “Art is not for artists and connoisseurs alone. It should be for the people.”

*****

Art isn’t only to illuminate horrors of the past. It’s to envision, to hope for the future. So yes there is “Birmingham Totem” printed after the 1963 bombing of the Birmingham church. And there is the series of “Wanted Posters” that summon up all the demons of

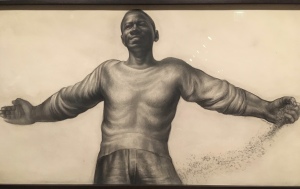

Oh Freedom – Charles White (1956)

past enslavement and degradation post slavery. About that group of works, done in 1969 to 1971, White said: “Some of my recent work has anger. I feel that at this point I have to make an emphatic statement about how I view the expression, the condition of this world and of my people . . . I guess it’s sort of finding the way, my own kind of way, of making an indictment.” But there is also the ecstatic “Oh Freedom,” expansive joy in the face of the subject, with the vigorous open-handed casting of seeds (in my mind, the intellectual seeds falling on fertile soil of the oppressed).

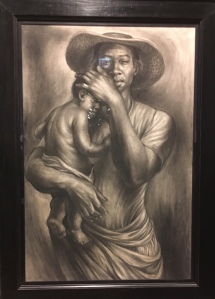

Look also at the determination in the eyes of the woman depicted in “Ye Shall Inherit the Earth.” I dare you to think that this woman will allow her child to inherit an earth like the one into which we have been born. She has her eyes on the prize and will protect not only him, but all children. Of course the title is a reference to “Sermon on the Mount,” but keep in mind that in 1953, when he drew this piece, he could not marry his wife in the state of Michigan; and that he could not easily

Ye Shall Inherit the Earth – Charles White (1953)

find an apartment to rent in the city of New York. To live in this land was not his birthright, and to imagine it, well, that almost smacked of treason.

In “Hope for the Future” and in “The Children” White again turns to a rendering of the child as a symbol of what is possible. Where can we go from here, he seems to be asking, how can we extricate ourselves from this dilemma in which we find ourselves? It is certainly the same question revolutionaries ask themselves today, knowing that hope for our future lies with those recently born. And, perhaps much like Charles White, here we stand trying to figure out how can we prepare for that future with the best possible art? The way Charles White does it, as revealed in this exhibit and these pieces in particular, is by showing that the best art is also the best propaganda, the best propaganda is the best art. How do you convey, with the necessary ambiguity to express the shifting ground on which you are standing? Look at the massy workers’ hands — I don’t know another way of describing the strength, the weight, the solidity of those hands — gently holding the child in “Hope for the Future.” Is she looking off to the side, and if so what is she seeing?

Hope For the Future – Charles White (1945)

Is she presenting us with a gift, this child, this future? Are “The Children” looking through the window with confidence, anticipation, hope . . .or is it with fear? Now that we see it, it is ours to do with what we will. It is our future now.

*****

I saw the show for the second time on the Thursday five days before the exhibit closed (Thursday nights are free at the AIC). It was much more crowded than the first time I went, and from the moment I entered I knew I was among a group of people who were there not simply to be seen at the latest big exhibit. These were folks who really engaged with the art, some who were, like me, old enough to be contemporary with some of his working years; others born long after he had passed on (he died at the young age of 61 in 1979). It was a conversation starting crowd, because of the excitement with the art and what it represented. Like when I first

The Children – Charles White – (1950)

came into the exhibit hall and looked over the shoulders of three older people no longer looking at “The Cardplayers,” but talking about what was life like in the 1940s during the war, and what did it mean to throw all the effort into the war, what did that mean for artists, and the older man, trying to remember, the word was right on the tip of his tongue, he couldn’t quite find it, it had something to do with limited quantities of goods available in stores, and just then a younger man, standing next to me, interrupted to say the word, and they all said Yes! Rationing, that’s it! And how do you know about rationing? And so the conversation continued with young and old appreciating each other and then talking about what they appreciated in the art work. And then they moved on, new friends made and exchanging views until, much later in the exhibit they shook hands, even embraced and bid each other good bye.

It was a conversation starting crowd. The secret smiles between two people as they saw the same things in the drawings. Yes this is my favorite in the whole show. I really like the “Wanted Posters”! I don’t know how he created this sense of motion with his pen and ink. And near the end, I found myself standing next to an older man, perhaps my age, who wondered why it had taken so long for a show like this to be mounted. He told the woman standing next to him, I don’t give the Art Institute credit really. They should have done it a long time ago. Of course I’m glad they did it now. You notice one thing about his work, he tells me, and that is the large hands and feet, the parts that engage in work. The emphasis on these, and his voice trails off. And then he begins to tell me, you know why there are so few oil paintings? It’s because oils are expensive, and he never had enough money to spend on oils. Well, maybe this is true. But I cannot get out of my mind Charles White’s own words, that art is not simply for the artist or the connoisseur but, most emphatically, for the people. And his work was displayed and copied and shared everywhere. Prints are a form adapted to this kind of art. Often people’s first exposure to a Charles White print was a poster on a telephone pole. “Ye Shall Inherit The Earth” was used as a poster to advertise a 1960 NAACP rally in Los Angeles.

It is disappointing that the mural — “Struggle for Liberation (Chaotic Stage of the Negro, Past and Present)” — Charles White designed for the Hall Branch of the Chicago Public Library was never installed. He began the mural in 1940, near the end of his WPA days

Study for Struggle for Liberation (Chaotic Stage of the Negro, Past and Present – Charles White (1940)

and before he and Elizabeth Catlett went into the South to gather material for the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship. Striking out from the left panel of the mural is the insurrectionary John Brown, while more modern forms of protest form the core of the right panel. A color study for the mural showing both panels is in the show, and it gives some idea of his bold ideas. The exhibit also presents a study for the mural, “The Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in America,” the result of the Rosenwald Fund

Study for the Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in America – Charles White (1943)

fellowship, and still installed at Hampton University in Virginia. The text for the exhibit identifies fourteen figures in the mural, including his contemporaries Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, and Leadbelly. I listened in to the conversations around these murals, to the excited identification of the people in the murals, to the careful examination of the features of the black and white studies for the mural (Robeson and Denmark Vesey, for example).

Charles White grappled with the idea of how to introduce new ideas into widespread discourse all his life. Roque Dalton wrote that “Poetry, like bread, is for everyone.” Bertolt Brecht or maybe Vladimir Mayakovsky perhaps wrote, “Art is not a mirror held up to reality but a hammer with which to shape it”; Both certainly could have said this: it is congruent with their writing and their philosophy. There is no doubt that Charles White, along with these other titans, saw his pen and brush as his weapon: Art is, after all, not for the artist or the connoisseur but should be for the people.

*****

Huntington Museum acquires “Soldier”